Boxer in China

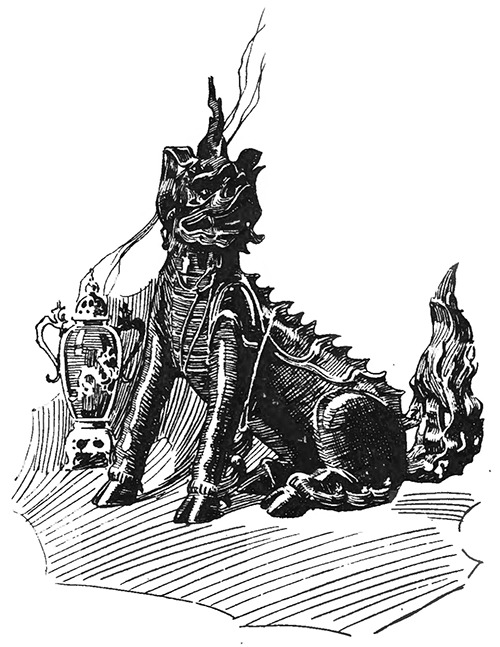

The original Boxer statue was a bronze qilin incense burner about 20 inches tall. Its neck was hinged so that incense could be burned inside it. The tail appears to have been removable, perhaps so that ash could be removed more easily. How this incense burner was used, how old it was, and what its significance was to the Chinese family who first owned it, are questions that can only be answered with fragmentary historical evidence.

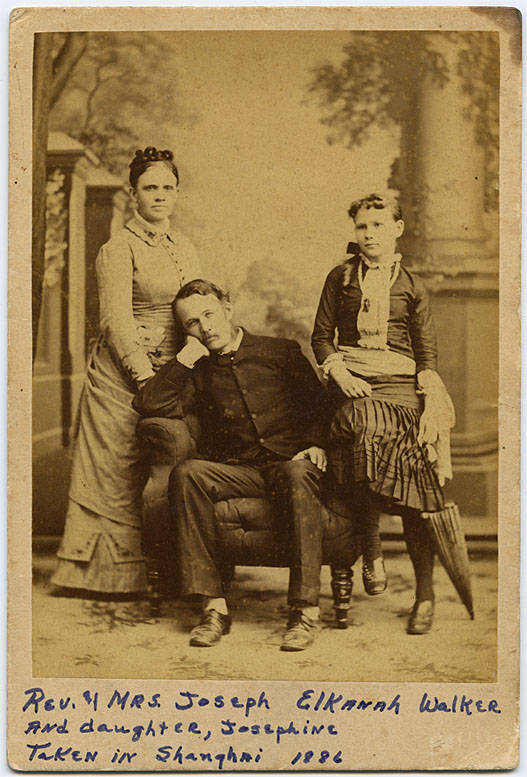

The main source of information we have about Boxer's origins are the words of the person who brought it from China to Oregon around 1896: Joseph Elkanah ("J. E.") Walker. According to a letter that he wrote decades later:

It was an heirloom in one of the old Shaowu families who came to Shaowu many generations ago. Such figures are used as signs by first-class drug stores, and stand on the counter. [...] On gala days Boxer would have sticks of burning punk [incense] down in his body, the smoke from which would pour out of his nostrils, and so add to his formidable appearance.

The tradition of placing bronze incense burners on pharmacy counter that Walker described may have been a local custom. Shaowu is a town in Fujian Province of southeastern China. Photographs of traditional pharmacies in other areas of China do not commonly show similar figures on their counters. A description of traditional Chinese drug stores in the north of China illustrates how they appeared in that region:

The store usually occupies one to three front rooms. No show window is provided, but the permanent signs such as "Most reliable drugs from all provinces"; "Ginseng and Deerhorn a speciality"; and so forth serve as the only advertisements. [...] The prescription counter occupies the very front of the front room, while the money counter often stays in the rear, for greater safety perhaps. Numerous herbaceous drugs are placed in rows of labeled drawers built against the side wall. On the top shelves, above these drawers, are porcelain containers with lead lids in which are kept powdered drugs, pills, mixtures and minerals. [...] Other furnishings of the fron room consist of a few chairs and one or more tables. (Chen, "Chinese Drug Stores," Annals of Medical History, Summer 1925)

The family in Shaowu might have chosen to display this particular incense burner due to its symbolic meaning. A qilin is an animal from Chinese mythology. Like a griffin or a unicorn, the qilin mixes together the characteristics of several animals. Its legs and antlers are from a deer; its scales and whiskers are from a carp; its tail is like that of a lion or an ox; and its face resembles a dragon. The qilin was believed to be a wise and beautiful magical being that would appear in order to signal the birth or death of a great ruler or sage. It was so peaceful in nature that it would not crush the grass by walking on it, but instead would fly or walk on water. Known as kirin in Japanese, this mythical animal symbolizes good luck, prosperity and fertility. As such, the Chinese family who owned might have considered it auspicious to display it in their place of business.

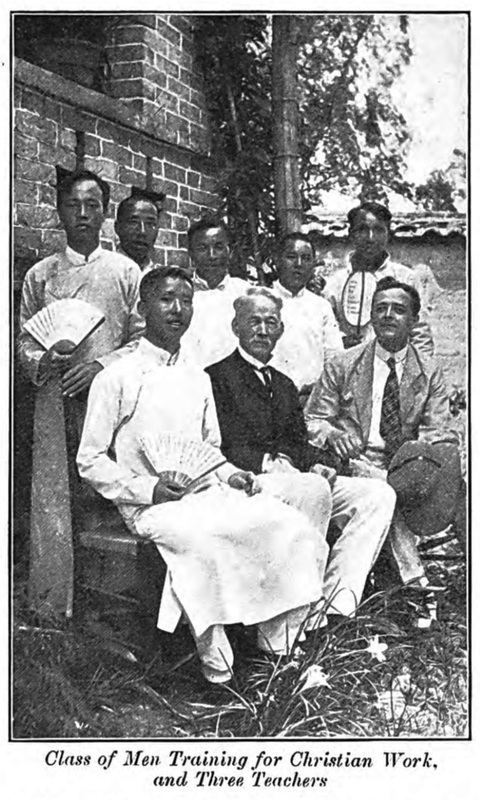

In later years, members of the Walker Family were careful to explain that Boxer was not an "idol," but rather a "trademark," "heirloom," or "sign" of the family that owned it. It is possible, of course, that Joseph Elkanah Walker misunderstood the significance of the incense burner. Walker was a Christian missionary in Shaowu. In this role, he was working to convert local people to Christianity, and therefore would not have been the most sensitive interpreter of traditional Chinese customs. On the other hand, he was much more familiar with local customs than any short-term Western visitor would have been. He first came to Shaowu in 1872, then moved their permanently with his family in 1875. He would live there for over 50 years. He became fluent in the Shaowu dialect knew many of its residents. (For more on the Walkers' work in China from a Western point of view, see: Kellogg, Work of the American Board Station in Shaowu, Fukien, China; Shaowu: 1915.)

According to Walker, he bought Boxer from its owner for $5, which adjusted for inflation would be equal to about $175 as of the 2020s.

This currency was worth more in Shaowu at the time, though, in terms of local wages. Nineteenth century China suffered from widespread poverty, caused in no small part by imperialist Western policies. The average wage for a Chinese worker in the 1880s was around 2.5g of silver per day, which was equivalent to about 10 cents in contemporary US dollars. Thus, the price Walker paid for Boxer was equal to around 50 days of wages in China -- but only about 4 days of wages in the United States. This may help to explain why Boxer's original owner was willing to part with a "family heirloom" for so little money. It was not much for an American, but it was a significant amount in the local economy. A Walker Family descendant believed that it was sold in order to settle a debt. (For more information on historic incomes in China, see: Allen, R.C. et al, "Wages, prices, and living standards in China, 1738–1925," The Economic History Review, 64: 8-38.)

After Walker bought the incense burner -- probably sometime in the 1880s or early 1890s -- he appears to have kept it in his home at Shaowu for a time. There is no known record of exactly when he brought it to Oregon, but it is likely that he packed it among the gifts he was bringing back for friends and family when he came to visit them in 1896.