1890s-1900s: The "College Spirit"

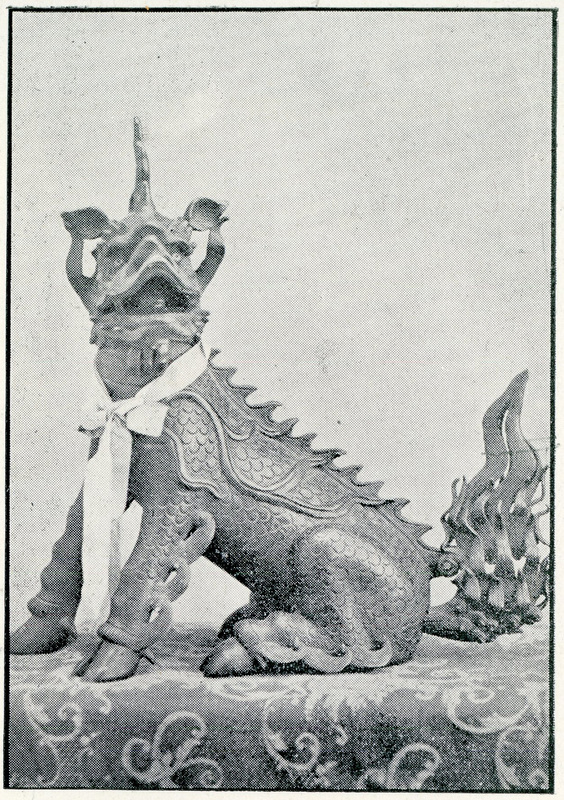

Joseph Elkanah Walker, a graduate of Pacific University, visited his mother in Forest Grove in the 1890s. He brought with him a bronze qilin incense burner that he had purchased in the town of Shaowu, China.

Joseph, or "J. E." as his family called him, had been living as a missionary in Shaowu since 1875. Every few years, he crossed the ocean to visit family in the Oregon town where he had grown up. His parents, Elkanah and Mary Richardson Walker, had been among the earliest immigrants to the Oregon Territory. The Walkers had helped to found Pacific University by donating part of the original land for its campus.

There is no clear evidence for exactly when J. E. Walker brought Boxer to Oregon, or exactly when it was given to Pacific University. According to some accounts, he gave the statue to his mother, who then gifted it to the school. This would suggest Boxer was donated in 1897 or earlier, since Mary died that year. Several other early sources suggest that it was J. E. himself who donated Boxer. One early article in Pacific's student newspaper said that J. E. Walker gave it to the school in 1894. Another stated, "In 1898, while here on a furlough, Mr. Walker presented the image to P.U. Such a gift was a valuable curiosity, and was placed in the alcove in the chapel" (The Index, Apr. 10, 1910, p. 2). This latter statement seems to match most closely with known facts, as J. E. Walker was indeed visiting Oregon between 1896-99 while recovering from malaria. No hard evidence for any of these dates have been found, however, so the precise time and manner of its arrival at Pacific remain unknown.

In any case, by 1899 (but possibly several years earlier), the bronze incense burner from Shaowu was put on display in the chapel of Marsh Hall. There, the statue was in the company of other treasured possessions of the university, including portraits of the school's founders which hung on the walls nearby. The chapel where it was placed was the largest meeting room at the college, and it hosted regular talks by students, faculty and visiting speakers. It was probably around this time that students began to take an interest in the statue. An early article in the college newspaper stated: "We had become after many years of relation with Boxer much attached to him. He was generally known by the students as the 'College Spirit.' Boxer had until his departure been at class feeds and picnics and took general interest in student activities."

All this led up to the key event in Boxer's history at Pacific: the first time students took the statue.

To understand how and why students first stole him, it is helpful to have a little context about college life in the 1890s. This was a time when colleges in the United States were transforming from their British-American colonial roots into the all-around academic and cultural institutions that we know today. Subject majors, a regular 4-year course of study, residential halls, college sports teams, social fraternities and sororities, school colors, mottoes, songs, yearbooks, newspapers, and many other aspects of college life that we take for granted today became popular then for the first time.

A new-found excitement over school spirit infected the entire student body at Pacific. Rivalries were in fashion. Students began to band together into groups that strongly emphasized insider versus outsider identities, with accompanying initiation rites and symbols. Unfortunately, rampant hazing of new members and pranks played on outsiders were also a part of this culture.

When a minister who had recently come to Pacific from Amherst College -- a Massachusetts men's school that was at the forefront of this new college culture -- gave a speech on pranks in the Marsh Hall chapel, Pacific's students were all ears. The scene was described in later years:

Years ago a Congregational clergyman, Rev. Mr. Dunning spoke to the students and in the course of his remarks told of student days at Amherst College. He referred to several exhibitions of college spirit at that institution and mentioned how a statue in the college campus had been removed from its location and hauled out of the city to grace a class banquet... . This story fired the Pacific University students with a desire to do the same thing with some fixtures about the campus. The Chinese idol [i.e. Boxer] answered the purpose. It was 'swiped' and made to preside at the banquet table... . The faculty made attempts to have the gift of the missionary brought back but all efforts were futile. (Forest Grove News-Times, June 22, 1911)

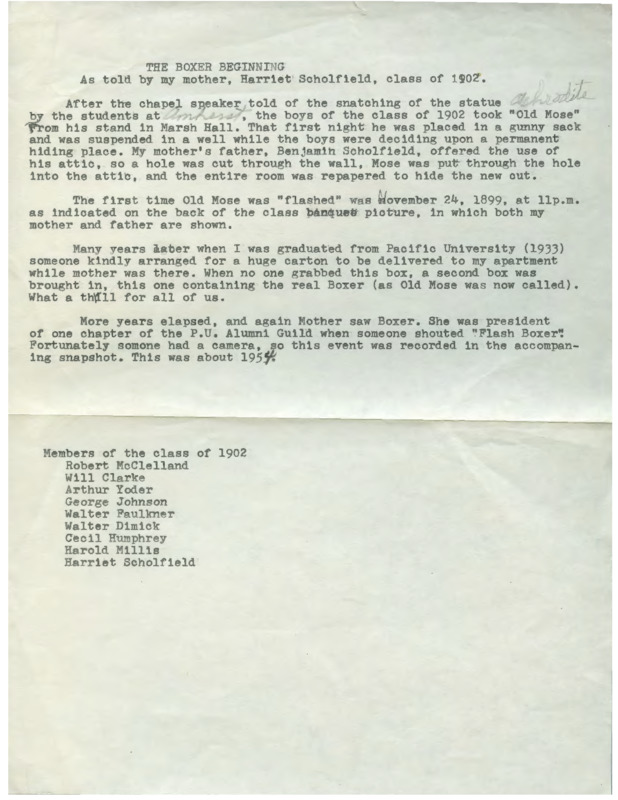

It was the Sophomores of the Class of 1902 who did the deed. After taking Boxer from Marsh Hall, they cut a hole in the wall of the attic of a family member’s home, put the statue inside and then papered over the opening. A month later in November 1899, they brought him to their class banquet, where they displayed him alongside other trophies signifying their status and spirit: banners, pendants and festive canes. The symbolism was obvious: the statue, already known as "The College Spirit," was the possession of the Class of 1902, which therefore could brag that it had the most spirit of any group on campus.

It wasn’t long before the student newspaper was publishing coded poems and statements about the theft. Some authors — presumably sophomores — celebrated their audacity. Others lamented:

Will not our plea enlist some heart?

Will no one come to take our part?

Must we, aye, for our spirit sigh?

Some one will surely help us try

To find that Spirit.

As noted above, students originally called the statue "The College Spirit." It would be a few more years before they began to call him "Boxer." This latter name appears to have caught on around 1902, arising at least partly because students did not know what kind of animal Boxer represented (a qilin). At that time, most Americans saw Chinese culture as exotic and strange. Though they might acknowledge China's ancient history, that did not mean that they treated it with the same respect they held for European history. In practice, this meant that Pacific students saw the statue as an amusing foreign mystery that was more fun to speculate about than to actually research.

Pacific students could have asked local Chinese-Americans about the College Spirit, but they never appear to have done so. Instead, they guessed. Was the statue a dragon? A unicorn? No; the consensus on campus was that it was a dog; perhaps a short-nosed breed of dog, like a bulldog or... a boxer. When that perception mixed with news of the Boxer Rebellion in China, the name stuck. For many decades after, students said that Boxer was a Dog.

What did Pacific’s administration and faculty think of all this? Naturally, they were very unhappy about the theft of a valuable gift to the university. Recovery efforts were unsuccessful though, and were soon abandoned.

For decades, Pacific's administration would view Boxer as an essentially grassroots phenomenon that was both literally and figuratively in the hands of students.